Ruby on WebAssembly

日本語で読む 🇯🇵

TL;DR: WebAssembly is here! Already familiar with it? Check out the wasm gem to get started.

Welcome to 2018, where some of the most exciting innovations are happening in the compiler space. Sure, there’s things like AR, VR, and machine learning on the bleeding edge, but don’t discount those technologies as old as computing itself, the software responsible for translating the source code we write into something the machine can actually understand. Much of this resurgence is thanks to LLVM, the modular compiler infrastructure project. Why is it such a big deal? This Wired article from 2013 summed it up quite well:

The hope is that LLVM will usher in a new era of software development where applications can freely move from machine to machine and even from processor to processor.

In the five years since, this has largely come true. How we build software has fundamentally changed with the introduction of LLVM and the modular paradigm it embraces. It offers a radical rethinking of portability, optimization, language implementation, and the entire compilation lifecycle. If you want to go deeper, I recommend this overview of LLVM by Chris Lattner, its principal author (and founder of Swift, no less). He was also interviewed on the Accidental Tech Podcast last year.

What does all this have to do with the web? Well, from the very beginning (1995 in this case), programming for the web has always meant one thing: writing JavaScript. Even after 23 years of criticism and controversy, it’s still the web’s programming language. Despite a lack of competition to force it, the language has still matured and evolved nicely, helping it stay relevant. The browser too has kept pace, growing from a viewer of statically-linked content to a full-on application platform, driven by the demands of billions of users and companies seeking a foundation on which to build their fortune. There is, however, one thing holding the browser back from being a proper application platform. From that same Wired article above:

The rub is that JavaScript is a relatively simple language. It can’t do everything other languages can do, including Java and those venerable creations, C and C++. What we need is a way of running any application, written in any language, on any machine, without a whole lot of compromise—and that’s where LLVM is headed, at least in the eyes of some.

To be a platform on par with your desktop or mobile OS, the browser must free itself from the one language it has ever known. Namely, its programming environment should be defined at a lower level, just like other platforms. It should have its own assembly language, still abstracted from specific hardware, but as close to machine code as possible. This was the goal of asm.js, a project started in 2012 to define a subset of JavaScript, restricting it only to concepts which would make it an ideal target language for compilers. This is where the history of LLVM and asm.js come together, and a new tool called Emscripten, an LLVM-to-JavaScript compiler created by Alon Zakai, made it all possible. We could now compile programs written in C and C++ to JavaScript, like so:

C/C++ → LLVM → Emscripten → JavaScript (asm.js)

Check out the slides for Alon’s “Compiling to JavaScript” talk and his CppCon 2014 talk on Emscripten and asm.js to learn more. With asm.js, we now had the beginnings of an assembly language for the web, which could be standardized and integrated into every browser, and that’s exactly what happened. In 2015, cross-browser work started on WebAssembly to further define a portable, efficient binary instruction format and safe virtual machine for the web. (See also Brendan Eich’s post, “From ASM.JS to WebAssembly”). In just over two years, the community developed a specification, iterated on prototypes, wrangled the biggest companies responsible for the web platform, and shipped WebAssembly in all major browsers. This is a monumental achievement which is hard to overstate. Perhaps, this is the way it should have been from the beginning, the browser providing a low-level compilation target where any number of languages could be used to program the web, and existing native tools, libraries, and applications could be brought along as well. Then again, who could’ve predicted what the web was to become and the demands placed on today’s browser. Nevertheless, we can be happy it’s here now and look forward to the potential it holds. See why Mozilla thinks WebAssembly is a game changer for the web. If you’d like to play around with it right now in the browser, check out WebAssembly Studio.

Bringing Ruby to the web

People have been using other languages on the web for years, but they’ve had to do it through JavaScript. Perhaps the most popular example of this is CoffeeScript. Started in 2009, people who were tired of JavaScript (or what it was back then) now had another option: write in a syntactically-enhanced language, more similar to Ruby and Python, and “transpile” it to plain JavaScript. Brilliant! Over the years, there’s been an influx of these source-to-source compilers — the list of languages that compile to JavaScript is…impressive. Ruby is no exception: we have the most-excellent Opal.

There are some practical shortcomings to this source-to-source approach, like efficiency and performance, losing out on low-level optimizations, for example. Some criticisms are rooted in principle, as in, why should we have to contort ourselves to meet the demands of JavaScript? Before WebAssembly, the answer was simple: because you have no other option. Now that we do, the race is on to take advantage of this new compilation target and welcome other languages to the web platform. How exactly do we bring another language to the web? For native languages like C and C++ which already compile to LLVM, and others implemented in LLVM themselves like Rust, the process is straightforward: just target WebAssembly in your compiler toolchain. For dynamic languages complete with an interpreter and virtual machine of their own, like Ruby, it’s a bit more challenging.

To see why, let’s look at Ruby’s primary implementation, MRI, also known as CRuby. All programming languages are much more than just a syntax specification — they’re also defined by how the language is implemented and the context of where it’s used. For Ruby, this has traditionally meant a comprehensive ecosystem of tools dependent on a Unix-like environment, complete with a file system, compiler toolchain, standard libraries, network, and everything else you might expect an operating system to provide. These are the expectations of MRI/CRuby, and that’s fine — the context of where Ruby is used, like on a web server running a Rails application, perfectly fits this model and plays to all of its advantages.

However, when we change that context, like distributing a Ruby application to an end user, things start to break down. We can’t expect people, developers and regular users alike, to have our desired Ruby interpreter installed locally with the correctly-versioned gems for every application. It would be completely impractical. We could get around it though — we just need to ship an entire Ruby interpreter along with our app. Don’t scoff, because it is actually possible. Traveling Ruby is an impressive project to create self-contained Ruby app packages for Windows, Linux and macOS. Minqi Pan gave an excellent talk at RubyConf 2017 on packing a Ruby application into a single executable, demoing a project which creates a virtual filesystem in memory and other magical things to make it work (video and code). Although I don’t know the approach they took, my favorite app example (and perhaps the most popular Ruby desktop app) is Sonic Pi, the live coding music synth.

While this type of “interpreter packaging” approach works, there are limitations, one of which being its sheer size. For perspective, a typical, fresh install of Ruby 2.5.1 on macOS (using rbenv install 2.5.1) shows 20.7 MB over 1,396 files. The Traveling Ruby compressed tarball is 6.7 MB (19 MB uncompressed) and the single executable from Minqi’s project is 40.8 MB (34.1 MB compressed). This isn’t really a huge concern for desktop apps, like Sonic Pi, but it’s a different story on the web. Even with some websites pushing 10 MB these days (looking at you, NYTimes.com), this is unconscionable — and we haven’t even factored in our app code yet! And It’s not just file size, MRI/CRuby is also fairly slow to start up and has a large memory footprint.

While it might be possible to put the entire MRI/CRuby interpreter in the browser, it doesn’t seem practical, maybe not even necessary. It’s certainly not the only Ruby implementation out there anyways. If only we had a more efficient, lightweight one, where we could pick only the relevant parts of the interpreter, and compile the whole thing down to a small, manageable binary. Well, we do!

Introducing MRuby

If you’re not yet familiar with MRuby, you really should be. In my opinion, it’s one of the most exciting things happening in the Ruby community today. A project led by Matz himself (yes, the creator of Ruby), the MRuby project was started in 2012 to be an implementation of the language suitable for “eMbedded” use cases where system resources, like memory and storage, are limited (for example, when programming a Washlet). It’s also fully modular, meaning instead of installing one big, monolithic interpreter, à la MRI/CRuby, you can customize it just the way you want. Don’t need a file system or network access? Leave it out! Want to limit the user’s power in what they can script? You can do that too. MRuby lets you build the interpreter that you desire. While it certainly has limitations — it’s not “full Ruby” as we know it — it offers substantial benefits over the language’s primary implementation, given the right context. If you’re looking to learn more, I recommend Zachary Scott’s pitch for MRuby and this interview with committer Daniel Bovensiepen.

Along with a rethinking of the interpreter architecture, MRuby also opens up some new possibilities, one of which is particularly interesting to us here: the ability to compile Ruby scripts to native code. This is a boon for distribution. Being able to create a single, small binary of your app means Ruby becomes ultra portable. Projects like mruby-cli make it easy to produce standalone executables for all major platforms from any machine. We can also embed MRuby bytecode directly into a C program, which we can then compile with clang, the LLVM frontend for the C language family. The compilation flow looks like this:

Ruby script → MRuby bytecode → C → clang → LLVM → native executable

Are you getting the idea?

From Ruby to WebAssembly

If we can target LLVM, we then have a path to WebAssembly. Recall that Emscripten is an LLVM-to-JavaScript compiler. In 2015, Emscripten started gaining the ability to compile to WebAssembly, which means our path from Ruby looks like this:

Ruby script → MRuby bytecode → C → emcc (Emscripten Compiler Frontend) → LLVM → Binaryen → WebAssembly

It looks a little crazy, but it’s all starting to come together! One new thing here in the flow is Binaryen, which is a compiler and toolchain infrastructure library for WebAssembly (its name comes from combining “binary” with “Emscripten”). Alon also gave a talk on compiling to WebAssembly with Binaryen.

Let’s get our hands dirty and give this a try. First thing we’ll need to do is get the WebAssembly toolchain. Head over to the WebAssembly “Getting Started” page for details. After ensuring you’ve met all the development prerequisites, the first thing you’re instructed to do is download, install, and activate the Emscripten SDK, like so:

$ git clone https://github.com/juj/emsdk.git

$ cd emsdk

$ ./emsdk install latest

$ ./emsdk activate latest

I recommend cloning the SDK to a place where you put other developer tools. You’ll notice some of these tools are under personal GitHub accounts. Most seem to work for Mozilla, so it’s cool, and I imagine in the future they’ll be consolidated to more official places, like the WebAssembly GitHub org.

Next, you’ll have to run the provided script to set PATH and environment variables, like so: source ./emsdk_env.sh. The Emscripten SDK provides its own version of clang and node, which will likely conflict with the versions you use in your regular development (installing/compiling Ruby from source and building gems with native extensions failed with their versions, for example). Instead of running with each new shell, I added an alias to my .bash_profile so I can run wasm_init to activate the SDK only in the shell where I’m working with WebAssembly:

alias wasm_init="source ~/Developer/emsdk/emsdk_env.sh"

And that’s it — you now have an Emscripten/WebAssembly toolchain available.

Next, we’ll need to install MRuby. For convenient access to the command-line tools, like mirb and mrbc, I recommend using Homebrew on macOS: brew install mruby

On Linux, use: sudo apt install mruby libmruby-dev

Now, we’re going to build an MRuby interpreter for WebAssembly. To do that, first clone the MRuby GitHub repository with:

git clone https://github.com/mruby/mruby.git

cd into the mruby/ directory. Here’s where things get interesting. We actually build our MRuby interpreter by defining a build_config.rb file, a simple Ruby script itself, and running Rake. Here’s the default config in the repo, complete with some helpful boilerplate — the documentation also is quite detailed. For our needs, we’re going to replace the entire contents of the config file with this:

MRuby::Build.new do |conf|

toolchain :gcc

conf.gembox 'default'

end

MRuby::CrossBuild.new('emscripten') do |conf|

toolchain :clang

conf.gembox 'default'

conf.cc.command = 'emcc'

conf.cc.flags = %W(-Os)

conf.linker.command = 'emcc'

conf.archiver.command = 'emar'

end

This new config tells the MRuby build system to create a native compilation for the host system using the GCC compiler toolchain, or whatever the closest equivalent is on your system. On macOS, gcc --version shows, among other things:

Apple LLVM version 9.1.0 (clang-902.0.39.1)

Target: x86_64-apple-darwin17.5.0

This will build binaries for our 64-bit x86 host system. We now want to cross compile to target WebAssembly, and that’s where the CrossBuild block comes into play. Here we choose the clang toolchain and specify to use emcc (Emscripten Compiler Frontend) and emar (Emscripten LLVM Archiver). The -Os compiler flag is optional — it enables most optimizations, including those that reduce code size. Cross compilation is quite powerful — in another project, I’m creating MRuby iOS and tvOS frameworks, which contain all the static libraries and headers in a single package.

We’re now ready to run rake to start compiling an MRuby static library for WebAssembly. A build/ directory will be created containing two more directories: host/ and emscripten/. The static library we desire is at emscripten/lib/libmruby.a.

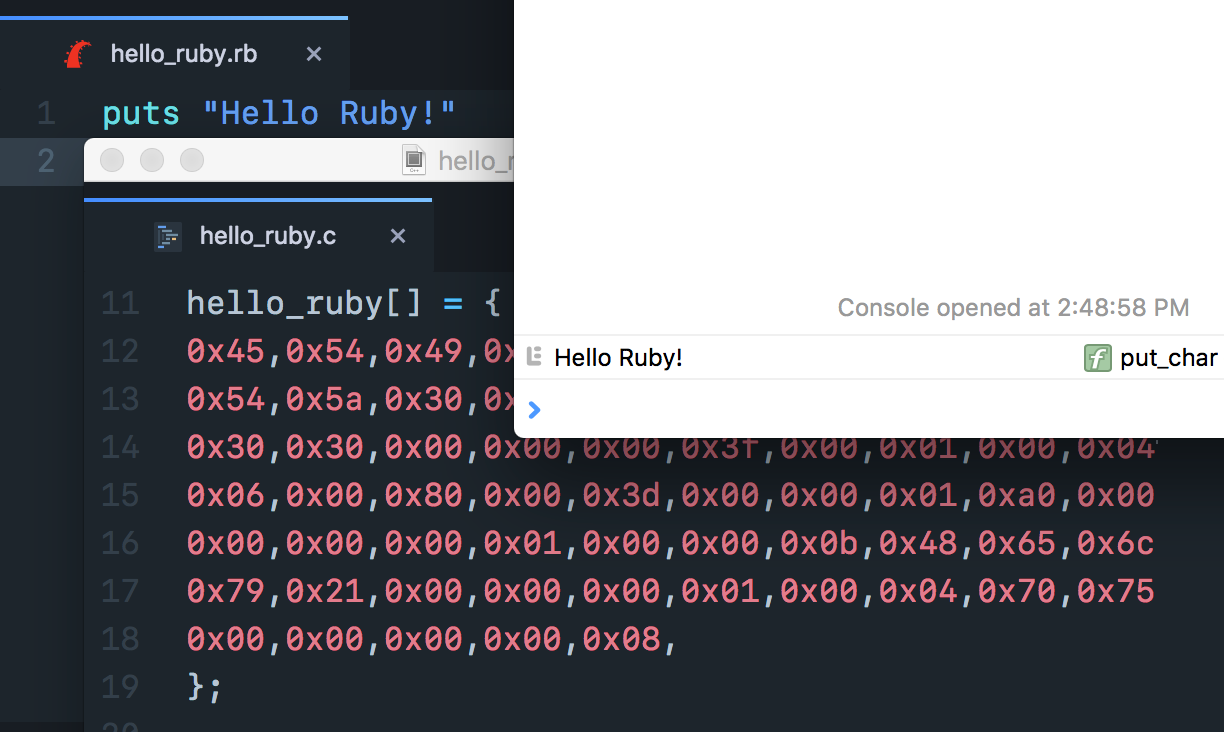

cd .. out of the mruby/ directory. Let’s now write a simple Ruby script to compile to WebAssembly, saving it to hello_ruby.rb:

puts "Hello Ruby!"

To generate MRuby bytecode from this script, we’ll invoke its compiler:

mrbc -Bhello_ruby hello_ruby.rb

Breaking this down, mrbc is the MRuby compiler and the -B tells it to create bytecode and place it in a C array named hello_ruby. Finally, hello_ruby.rb is the file we want to compile. The result will be a new C file named hello_ruby.c containing our array with hexadecimal integers representing our bytecode:

hello_ruby[] = {

0x45,0x54,0x49,0x52,0x30,0x30,0x30,0x34,0xcd,0x4c,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x65,0x4d,0x41,

0x54,0x5a,0x30,0x30,0x30,0x30,0x49,0x52,0x45,0x50,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x47,0x30,0x30,

0x30,0x30,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x3f,0x00,0x01,0x00,0x04,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x04,

0x06,0x00,0x80,0x00,0x3d,0x00,0x00,0x01,0xa0,0x00,0x80,0x00,0x4a,0x00,0x00,0x00,

0x00,0x00,0x00,0x01,0x00,0x00,0x0b,0x48,0x65,0x6c,0x6c,0x6f,0x20,0x52,0x75,0x62,

0x79,0x21,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x01,0x00,0x04,0x70,0x75,0x74,0x73,0x00,0x45,0x4e,0x44,

0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x08,

};

This is still just static data — we’ll need to do a bit more to load and execute it. Let’s append the following to our hello_ruby.c file containing our bytecode array:

#include <mruby.h>

#include <mruby/irep.h>

int main() {

mrb_state *mrb = mrb_open();

mrb_load_irep(mrb, hello_ruby);

mrb_close(mrb);

return 0;

}

This snippet does a few things. First, it includes the core MRuby and intermediate representation (bytecode) headers. In the main() function, we open an MRuby context with mrb_open(), load and run the bytecode array with mrb_load_irep, and finally close the context. Simple!

Our hello_ruby.c file is now ready to be compiled using Emscripten, targeting WebAssembly. We’ll invoke the emcc command like so:

emcc -s WASM=1 -Os -I mruby/include hello_ruby.c mruby/build/emscripten/lib/libmruby.a -o hello_ruby.js --closure 1

Let’s break it down:

emcc— The Emscripten Compiler Frontend (to LLVM)-s WASM=1— Emit WebAssembly-Os— Use optimizations including space saving, optional-I mruby/include— Look for the MRuby include directory here, containing necessary headersmruby/build/emscripten/lib/libmruby.a— Path to the MRuby static library we built earlier-o hello_ruby.js— Output to this file; The extension here is significant, which says to generate a JavaScript file (more on that below)--closure 1— Run the Google Closure Compiler to minify Emscripten-generated JavaScript; Optional, but another good optimization to save space

Two new files will get generated with this command: hello_ruby.wasm and hello_ruby.js. Fully optimized and minified, everything adds up to about 492 KB. Now you might be thinking, “Why are we generating JavaScript?! I thought we were finally replacing it!” Well, not so fast. Turns out this bit of JavaScript is going to help us out quite a bit. First, we can’t simply use a <script> tag like we’re use to load the .wasm file. Instead, the generated JavaScript will use the Fetch API to grab it (there are actually future plans to allow WebAssembly modules to be loaded like ES6 modules, using <script type="module">). The generated JavaScript will then compile the .wasm bytes into a WebAssembly.Module and instantiate it. Function imports and exports are also set, memory is configured and allocated, and other common services we expect the operating system to provide, like TTY for printing to the console, are emulated in JavaScript. If you dare, run the emcc command above without --closure 1 and explore the generated JavaScript in all its glory. This “Understanding the JS API” article will help you make some sense of it. Alon also has a guide for building standalone WebAssembly.

Now that we know why we need this bit of JavaScript, let’s write a simple HTML template to load it into the page, which will do all the hard work of fetching and running our hello_ruby.wasm binary file:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Ruby on WebAssembly</title>

</head>

<body></body>

<script src="hello_ruby.js"></script>

</html>

Save this file as hello_ruby.html. We can’t just double-click the HTML file and expect it to work — the Fetch API request will be blocked due to cross origin issues. Instead, we have to serve the file, which is easy enough with Ruby:

ruby -run -ehttpd . -p8000

This will start a simple web server and serve up static files in the current directory on port 8000. View our HTML file by going to http://localhost:8000/hello_ruby.html. Open up the web console and you’ll see “Hello Ruby!” 🎉

(Since people have asked, I use Atom with the City Lights theme. 😍)

That was a bit of work, so I’ve got something to make your experimentation a little easier…

The wasm Ruby gem

This entire build process above has been put inside a gem. Get it with:

gem install wasm

To use the gem, you must first have the WebAssembly toolchain set up, with emcc and emar available on the command line. Then, you’ll be able to use the ruby-wasm utility to compile Ruby scripts to a WebAssembly binary, and generate the aforementioned JavaScript and HTML files with ease. You can then serve the HTML page with ruby-wasm serve. Check out the gem repository on GitHub for all the details.

What’s next?

Like me, you’re probably wondering where we go from here. What does all this mean for Ruby on the web? What are the real opportunities, and which will only amount to fun experiments to explore the art of the possible? I don’t really have profound insights here, except to say that the most immediate opportunities will be in leveraging the obvious strengths of WebAssembly. I might put these into three broad categories: performance and efficiency, interoperability with the native world, and portability.

In the case of performance and efficiency, we now have access to a true compilation step where analysis and optimizations can take place. With LLVM, we can take advantage of the considerable optimization features that already exist, and the ones to come. While already fast and efficient, the WebAssembly virtual machine and runtime components will go through iterations of improvement over time as well. For Ruby, this means a smaller, faster, and more efficient interpreter in the browser, which will benefit the apps we choose to bring to the web.

Another exciting possibility is interoperability with the native world, by which I mean interfacing with software written in languages originally intended to be compiled to native code. There are thousands of existing libraries and tools that are written in these languages, and with the advent of WebAssembly, they can now be brought to the web. A great example of one such library already targeting the browser is the Simple DirectMedia Layer. SDL, for short, is a cross-platform game development library, providing low-level access to graphics, audio, and input. With the addition of supporting browser APIs, it’s now possible to port a game originally intended for a traditional native platform to the web. There are already some pretty cool demos of this, like Epic Games’ Zen Garden. The opportunity for us is to let the lower-level components continue to do what they do best, and use Ruby to orchestrate them at a higher, more conceptual level. As an example, this is precisely what I’m doing with another project of mine, Ruby 2D. It’s built on Simple 2D, a little graphics engine written in C that I built, which is in turn built on SDL. My next challenge is to get Ruby 2D running on WebAssembly. If interested in how Ruby 2D is architected, check out my RubyConf 2017 talk.

Finally, there’s portability, or the ability to take our Ruby apps and interpreter just about anywhere. MRuby is really the magical thing that makes all this possible. Because we can target clang/LLVM, or any C compiler toolchain for that matter, our Ruby apps can be compiled for any platform. To date, the focus has been on small, embedded computers (think IoT — I hope to get my hands on a Circuit Playground from Adafruit soon, maybe an Arduboy for fun too), but that will broaden in the future. A .wasm binary of our Ruby app could be ultra portable, running on the server or client side. Take AWS Lambda for example: while they don’t support Ruby today (boo), we could deploy a Ruby WebAssembly binary instead. It’s not only portable, but safer and more performant than running a Ruby script through MRI/CRuby.

There certainly is a lot of interesting possibilities on the horizon. One thing I don’t think will happen is the complete replacement of JavaScript in favor of Ruby (or any other language). Web browsers already ship with a very capable programming language and optimized virtual machine refined over decades. And writing JavaScript isn’t so bad anymore, especially with all the modern amenities ES6 provides. If we do want to use Ruby on the web, we have a really solid option with Opal, which is incredibly easy to integrate into and interoperate with JavaScript.

Lastly, I’ll just say that the line between what a “native” and “web” app will continue to be blurred. Progressive web apps and other approaches will mean that we developers get the best of both worlds, and end users will enjoy better experiences on the web, and with desktop and mobile apps that use web technologies. I imagine the conversations we’ll have around “Is it possible?” will be quite short (almost always, yes). Rather, the ones concerning “Is it good and how do we know?” will be much more lengthy and difficult. Who knows where we’ll end up — it’ll surely be a captivating journey.

So here’s my advice for anyone who wants to make a dent in the future of web development: time to learn how compilers work. — Tom Dale

Thanks!

I hope this foray into Ruby on WebAssembly was informative, and you have fun playing around with the wasm gem. If you want to leave a comment, you can reply to the tweet announcing this post. If you have ideas for the gem, or just want to explore ideas, feel free to open an issue. And as always, you can email me.

👋